Peccioli

Contemporary Art, History and Culture

Learn more about Peccioli

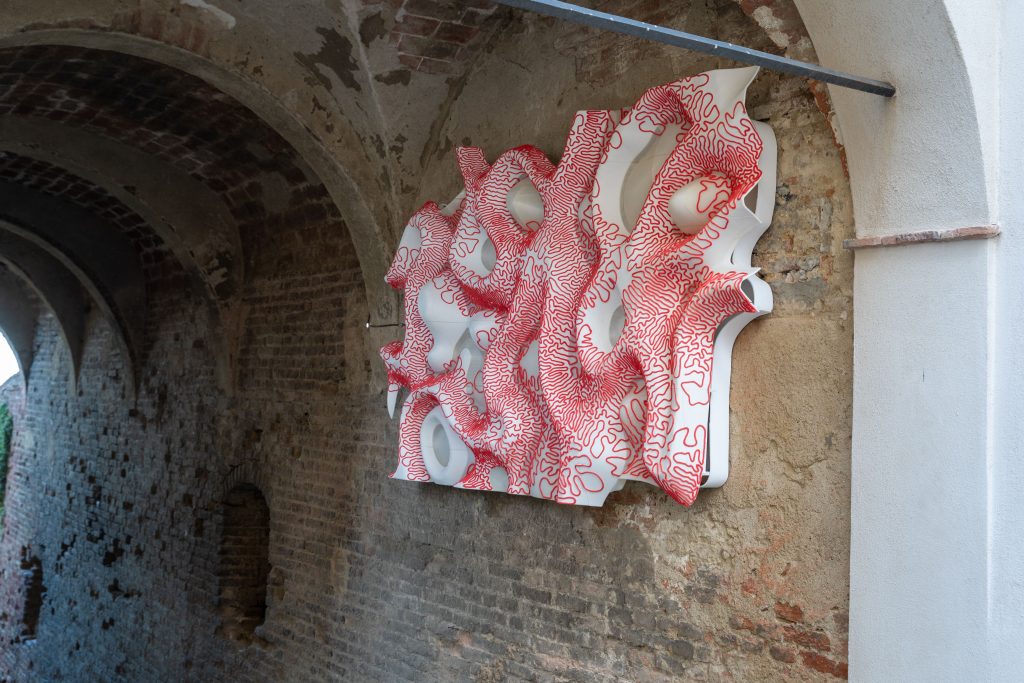

Medieval layout, chiassi – the steep alleys typical of these villages – an ancient parish church and a bell tower which is its symbol. A peasant past of which traces have not been lost, of course, the countryside of the Serre reminds us of it, but which we have not yet reached. Peccioli is not a village suspended in time: it looks ahead, to the future, to sustainability, to projects shared between the Municipality and its inhabitants. Witness the contemporary art installations inserted in the urban fabric, which have made Peccioli an open-air artistic laboratory.

The village of Peccioli develops around the ruins of an ancient medieval castle, surrounded by olive groves, vineyards and green hills. Still today it retains numerous elements of the architecture of the 12th century such as Pieve di San Verano, the chapel of Peccioli and Palazzo Pretorio. .

The name was firsly attested in a parchment of 793 such as Picciole, Petiole and Pecciori and it probably derives from the Latin term picea, a wild pinetree. Despite a place called Pecciole had given its title to a church in the 8th century, the history of Peccioli is known only from the first half of the 12th century.

The town is also mentioned in a parchment of 1061, received by the abbey of Poggibonsi by donation of a certain Marquis Alberto, son of the Marquis Obizzo, in which reference is made to the Petiole locality located upon the Era river.

The development of the village of Peccioli took place later in medieval times, around a castle that was under the jurisdiction of the Counts Della Gherardesca, who already owned numerous properties in the surrounding area.

In the 12th century the same Counts ceded the Castle of Peccioli to the Bishops of Volterra, who made use of it as a defensive stronghold of the city of Volterra in their fight against the Pisan expansion. Later, another Bishop ceded it to Pisa.

Over the centuries the Castle of Peccioli was gradually enlarged and strengthened under the rule of several owners. The village and the fortress located on the central hill, locally called “Castellaccia”, were encircled inside a first wall, whereas the southern part, the area of the Parish di San Verano, was excluded: this because in case of war or siege, the church had to be ready to welcome the believers and peasants who lived in the countryside, like all churches.

During the fourteenth century the Castle underwent the most important changes and extensions, which even today can be glimpsed, with a little patience, despite the numerous dismantling operations. These new fortifications have been attributed to Castruccio Castracani, a famous and valiant leader from Lucca, during the short period in which he was Lord of Pisa. The fortress was rebuilt on the “Castellaccia” hill, perhaps on the same foundations as the one that the Pisans had demolished two centuries earlier. It consisted of two imposing towers in terracotta bricks, connected to each other by a bridge, also in masonry.

The manor was truly imposing and inaccessible on the summit. The village, which in all those years had developed considerably around the fortress on all sides, was closed in a wider wall, which also enclosed the Pieve di San Verano, as the village had also extended to the south. The walls were divided into “curtains” delimited by square towers at the corners and round towers along the course of the curtain walls.

The Porta Pisana gate was not the alley today commonly known as “the alley of nuns”, but lower down, differently from what has always been believed. That alley was nothing more than a “walkway” along the walls that continued from the section that still remains to the entrance that was just below. This thesis is supported by the fact that the ancient medieval road that came from the lowland of “La Bianca”, that is from Via di Gello and therefore from Pisa, followed the same route along the current Via dei Cappuccini. Since before the construction of walls roads generally led to churches, which were the true centers of villages, this Via dei Cappuccini certainly continued towards the church of San Verano, following the same route as the current Via Borgherucci. It followed it by directly crossing the road “Via Nuova” (Via Mazzini), which at that time did not exist.

The Porta Pisana gate was then built in correspondence with that road, whose position, perhaps, involved the front part of today’s Burgalassi’s house, the shortcut with the staircase and part of today’s Marinari’s building. It is likely that the entrance was more or less in that point, also due to the immediate proximity of the corner tower that was demolished in 1872 on the occasion of the construction of “Via Nuova”, from which it was possible to control it and defend it from attacks by besiegers.

The arch of the Porta Volterrana gate is still visible today, in all its ancient solidity, in the middle of today’s Via Carraia, from which mostly all carriages accessed the castle, hence the name later assumed by the street. From this gate voyagers would reach the road to Volterra, Siena and Rome.

In this regard, we can mention a little curiosity: in an ancient letter, traced in the archive of a convent in Pisa, a friar from Siena, author of that letter, invited one of his confreres, who had to reach him from Pisa, not to pass through Peccioli because, he said, they had made him pay a very high “toll”.

Next to the Porta Volterrana gate both a watchtower, in a squared shape, transformed into a house, and a walkway, now called Via Bastioni, are still visible. This continues almost straight, with passages under the defense posts, along the entire eastern front up to the ruins of that round turret, called “dell’amicone”, recently demolished because it was unsafe.

From here the walls continued up to a corner tower, in a squared shape, in Via Corbiano, also transformed into a house, which, with a little patience, can be detected from the Piazza del Carmine below.

This tower connected with another one in a similar squared shape, which is at the corner of the building of the Gaslini Foundation, thus forming the defense curtain on the side of today’s Piazza del Carmine, which is commonly called Il Fosso, literally “the ditch”, as in ancient times the place supposedly hosted ditch for collecting the rainwater that came down from the castle and from the hillock of the fortress.

In 1163 the Pisan army besieged the territory and conquered and seized the castle. Following the defeat inflicted on the Pisans by the Genoese in the Battle of Meloria in 1284, Volterra passed under the protection of the Republic of Florence and thus laid the foundations for a new offensive.

The Florentine army managed to defeat the Pisan army and to conquer the village of Peccioli which from that moment came under the jurisdiction of the Republic of Florence. The Bishops of Volterra maintained only some rights on the village, including those to collect duties on the extractive activities that took place in the area. The rivalries for the control of the village between Pisa and Florence did not subside and only in 1293, with the Peace of Fucecchio, the village of Peccioli was definitively annexed to the possessions of the Republic of Pisa.

In 1362, however, a war was rekindled between Pisa and Florence and the Florentines, well aware of the strategic importance of the Castle of Peccioli, sent a strong army to the Val d’Era region under the command of Captain Bonifazio Lupi. The first attempt of conquest did not succeed. So a the siege of Ghizzano was arranged and the small castle surrendered on the condition that “everyone’s life and property be saved”.

Believing that the Castle of Peccioli was impregnable at that time, the Florentine army headed for Pisa and sacked numerous palaces, noble villas and simple houses in Cascina, Riglione and Putignano. The Pisan captain, who commanded the Castle of Peccioli, had left Peccioli right in those days to go to the countryside by Volterra, where it seems he had been engaged in a fact of arms. Those few soldiers who remained on guard, sensing the danger, hurriedly sent an envoy to Pisa, but fate made him fell into the hands of the Florentine army which, returning from Pisa, was again heading towards Peccioli. In the meantime, the Pisan Captain and his soldiers had managed to return to Peccioli in time and, to organize the defense in a hurry. Unfortunately, however, in the face of the predominance of the Florentines, commanded by Ridolfo da Camerino, there was very little to do. Among knights, infantry and crossbowmen, there were more than seven thousand men who surrounded it in a tight siege.

Although the Castle was well fortified with very solid walls on cliffs that favored the defense, the soldiers immediately realized that being considerably fewer than the Florentines, they could not resist for long and after ten days they came to terms. It was agreed that if after a further ten days there were no help from Pisa, the gates of the Castle would be opened and the lives of all people saved. As a guarantee, the defenders handed over some hostages who were sent to Florence. On 11 August 1362, the ten days expired in vain, the gates of the Castle were opened and the Florentine troops entered.

The Pisan Captain, however, did not want to give up and, believing of being able to resist for a long time, took refuge inside the fortress that stood on the top of the town, formed by two towers connected by a bridge. The General Ridolfo da Camerino then resorted to an ingenious strategy: he had a tunnel dug in the tuff bank on whose top a tower stood and, once the foundations were reached, he had wooden props placed there. Then, he invited the Pisan Captain to surrender. He rejected the invitation considering himself safe, so General Ridolfo ordered the props to be set on fire and the tower was ruined, destroying part of the fortress walls as well.

Seeing any resistance was useless, the Pisan Captain and his small gang, who had just had time to take shelter in the other tower across the bridge, surrendered and was imprisoned and sent to Florence.

It was then on August 28, 1364 when Peccioli with the whole Val d’Era returned to Pisa. In that year the Pisan troops under the command of Manetto da Jesi, just below the castle of Peccioli, defeated an army from Florence.

But, in October 1406, the Castle of Peccioli fell under the Florentine dominion, thanks to the nefarious work of Pietro Gaetani, a Pisan citizen, who by playing a double game, allowed the Florentine army to enter both the Peccioli Castle and all the others from the Val d’Era.

At that time the Republic of Florence was governed by the noble family Medici and under their rule, Peccioli became a center of reference for the neighboring villages, rising to the role of Podesteria. During the period of his Signoria (1479-1492), Lorenzo the Magnificent promulgated, in fact, a new administrative order and the local Communities were gathered in “Podesterie” and Peccioli itself was also the premises of a Podesteria: its jurisdiction included the Communities of Ghizzano, Fabbrica, Lajatico, Terricciola, Rivalto and Chianni.

Throughout the fifteenth century Peccioli suffered looting and devastation by cities and anti-Medici nobles and found occasions to rebel against the Florentine Republic when the opportunity arose: in 1431 Peccioli supported the invasion of its territory by the troops of the Duchy of Milan, led by Niccolò Piccinino, and in the sixteenth century the invasion of the troops of the Prince of Orange, who had previously besieged the city of Florence.

In 1531 Tuscany became a Grand Duchy and, with Ferdinando I de ‘Medici, the town was enriched above all in the sector of agriculture (vineyards and olive groves) and a new administrative order was created.

So, there was:

- The Municipality, made up of the Communities (the villages where castles once stood).

In the case of Peccioli the communities were those that today are the hamlets of the Municipality, such as Ghizzano, Fabbrica, etc. The Municipality had a single representative body: the Mayor.

- The Podesteria grouped the Communities and had two bodies: the Podestà and the Board of Mayors. The Podesteria of Peccioli included seventeen communities, namely: Peccioli, Ghizzano, Fabbrica, Legoli, Terricciola, Casanuova, Soiana, Morrona, Lajatico, Orciatico, Montecchio, Bagno (Casciana Terme), Chianni, Santa Luce, Riparbella, Strido and Castellina Marittima.

- The Vicariate which was the body above the Podesteria. Peccioli depended on the one of Lari, which also supervised the Podesterie of Lari and Palaia. The tasks of the Vicariate were almost the same of those of Prefectures, in use until recently, before the new regional order was introduced, but more extensive.

Subsequently, with Leopoldo I of the House of Lorraine the Vicariates and the Podesterie were suppressed.

With the submission to the Medici Grand Duchy, a period of peace and political stability began for Peccioli, which lasted until the advent of the Dukes of Lorena in power. They started the first works for the drainage and reclamation of the territory, which further favored the development of agricultural activities and wine production.

The Dukes of Lorena maintained control on Peccioli even after the end of the French domination, which occurred at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

On 27 April 1859, in fact, the last Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopoldo II Lorena, abdicated and on 11 and 12 March 1860 there was the “plebiscite” for the annexation to the Savoia Kingdom, in favor of which there were 838 votes by the inhabitants of Peccioli.

On 2 June 1946, Italy passed from a Monarchy to the proclamation of the Republic with 2863 votes by the inhabitants of Peccioli.